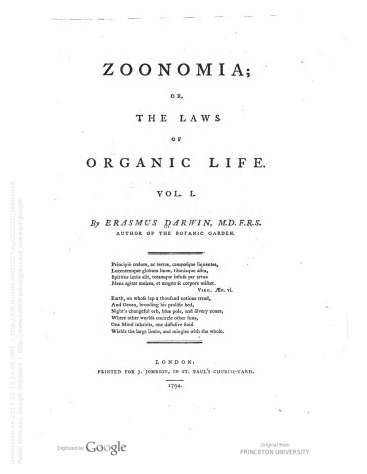

DARWIN, Erasmus, Zoonomia; or, the Laws of Organic Life, Vol. 1. London: J. Johnson, 1794(-1796).

Original citation: Idem.

Condemned: December 22, 1817.

§9: Books which professedly discuss, describe or teach impure and obscene topics.

Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) was an English physician and natural philosopher (naturalist). He was also the paternal grandfather of the profoundly influential naturalist and writer Charles Darwin. Erasmus died seven years before the birth of his grandson, however, so the two never met. Erasmus’ Zoonomia was formally condemned and placed on the Index as of 1817, when Charles was only eight years old. Interestingly, decades later, none of Charles’ own works was ever condemned, despite what many might assume as such texts’ conflicting interpretation of the natural cosmos vis à vis Catholic dogma.

Zoonomia is essentially a treatise in search of the kind of unifying scientific theory that the author’s grandson would later elaborate and publish in 1859 with On the Origin of Species. With an astounding amount of prescience, Erasmus stated in his book’s introduction, “A theory founded upon nature, that should bind together the scattered facts of medical knowledge, and converge into one point of view the laws of organic life, would thus on many accounts contribute to the interest of society” (2). It does not come as a surprise, then, that Charles had studied his grandfather’s work before embarking on his own vocation as a naturalist.

A cursory search of the contents of the first volume of the first edition of Zoonomia yields 18 instances of the words “sex” or “sexual.” Due to this technicality alone, one can imagine why this text may have originally been brought to the attention of the censors of the Congregation of the Index. Since most instances refer to sexuality in the context of zoology and biology in general, modern sensibilities would dictate that a proscription based on such a myopic reading was misguided, to say the least. However, a closer reading reveals more incontrovertible causes for it to have been forbidden. Darwin indeed waxes both scientific and philosophical on “irritations,” “pleasurable sensations,” and “exertions” in the context of various species of plants and animals throughout the text. And at least once or twice he specifically refers to the aforementioned “motions of the genital apparatus which are preparatory to the complete act of sexual union” so concretely indicated as verboten by Father Gardiner (1958: 64). The proof of a violation of canon law is thus self-evident if one is to follow Canon 1399 §9: Darwin writes, “…at the time of procreation the idea of the male organs, and of the female features, are often both excited at the same time, by contact, or by vision” (521). “Obscene” statements such as these were evidently sufficient for censors to deem this particular text forbidden.