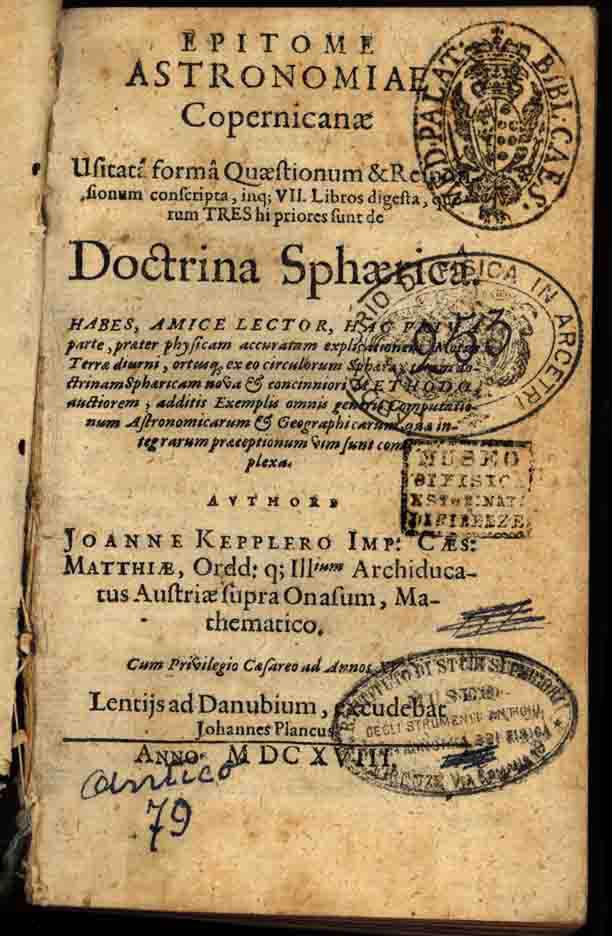

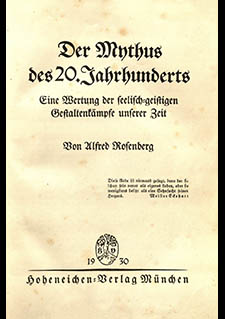

Read my latest article on the Index librorum prohibitorum in the May-August 2025 issue of The Truth Seeker here: https://publuu.com/flip-book/470081/1968145/page/24. The “flipbook” format replicates an actual codex magazine, but if you prefer a print copy you’ll have to subscribe ($35 per year for three issues).

I was previously unaware of this triannual magazine, which has been in existence since 1873 (!); it is billed as “The World’s Oldest Freethought Publication.” Its publisher, Roderick Bradford, reached out after reading my introductory blog post about the Index in the ALA/OIF “Intellectual Freedom Blog,” from 2018. With Bradford’s encouragement, I was able to expand on that piece, along with several other posts hosted here, to fashion a long-form article focusing on the last few decades of the Index‘s existence (c. 1920-1966).

This particular issue of The Truth Seeker also features various articles on the Scopes “Monkey” trial of July 1925, which brought the debate between faith/religion and science to national prominence in the United States. Lots to sink one’s teeth into, even one hundred years later.

I was also thrilled to share an issue (his article precedes mine) with S.T. Joshi, widely recognized as the foremost scholar of the life and works of American horror and science-fiction pioneer H.P. Lovecraft.

-RMS